1911 Quirks: Barrel Bushings

A lot goes into a semi-automatic pistol. There are any number of moving parts, both large and small, that have to work in unison so that the pistol fires and cycles itself safely and reliably. Most pistols share similar parts: barrels, extractors, ejectors, recoil springs, locking blocks, etc. And then there are barrel bushings, which are largely unique to the 1911 platform. Most pistols, even those that were developed during the same time period as the 1911, do not use barrel bushings. That begs the question: why does the 1911 have a barrel bushing, and what function does it serve?

Barrel Bushings: What Are They?

A less technical term for a bushing might be a buffer. In this case, the buffer functions between the slide and barrel, serving as a locking point for the barrel and controlling its movement during the cycling process. There have been more than a few handgun designs that use barrel bushings, albeit most of them are older. The first Colt 1903 Pocket Hammerless pistols, for example, initially debuted with a barrel bushing before it was quickly phased out. More recently, the discontinued Smith & Wesson 945 pistols used barrel bushings. However, barrel bushings are most associated with Model 1911 pistols, although not all 1911s available today have them.

Many newer 1911s and double-stack 2011s rely on a guide rod or a bull barrel in lieu of a barrel bushing, but the lion’s share of what is out there is wearing a barrel bushing. The 1911 platform is the only mainstream design still incorporating the design. Why?

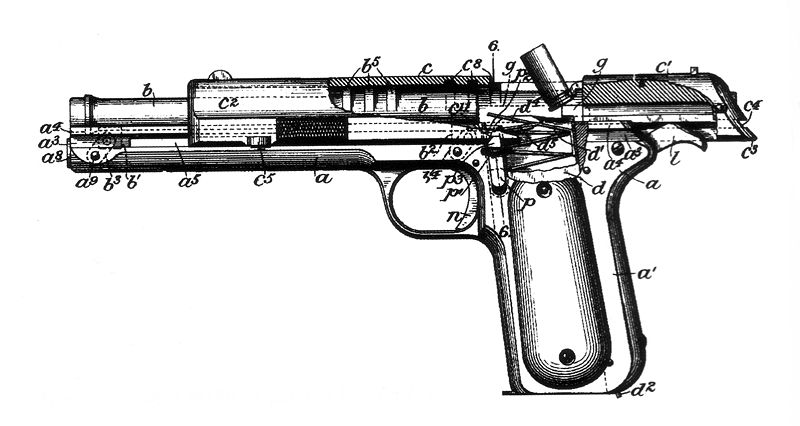

How Browning and Colt Arrived at the Barrel Bushing

Although the Colt Model 1911 was ultimately adopted by the US Army in 1911, it was the culmination of a decade of international politicking and seemingly endless trials to determine whether a semi-auto pistol was really viable to replace the existing Colt service revolver. At the time, the Army was shirking the .38 Colt cartridge and looking to return to a more powerful .45 caliber cartridge, so any new semi-auto pistol could not be made to the lowest common denominator of cartridges.

John Browning’s Model 1899 was the first slide-action auto pistol. It was accurate and reliable, and more than a fair share of Europe’s powers adopted the improved Model 1900 in .32 ACP. The problem is that this was a blow-back-operated design with a fixed barrel, and it fired a relatively low-powered .32 round. To get a more powerful cartridge in the same format, the slide and recoil spring would have to be beefed up to the point of impracticality.

Meeting The Demand

To meet the demand for a more powerful handgun, Browning developed a recoil-operated pistol with a locked breech. This locked breech became the well-copied Browning tilting lock design. When fired, the barrel cams down, guided by the slide and the frame, unlocking the barrel from the slide and permitting the slide to recoil rearward, strip out the empty case, and reload the next round thanks to tension from the recoil spring.

On a typical blowback-operated pistol, the recoil spring that brings the slide back home is mounted coaxially over the barrel itself. For a locked breech, the recoil spring had to be moved out of the way for the barrel to tilt and unlock.

The First Attempt

Browning’s first attempt at this was produced as the Colt Model 1902. It is a .38 ACP pistol that was meant to compete for the Army’s favor, although sporting versions were offered to the civilian market well into the 1920s. It featured the locking breech action and a recoil spring under the barrel. Interestingly, it did not have a barrel bushing per se. It took a page out of future designs by having a conical-shaped barrel to lock up the barrel to the slide at the muzzle. There was a noticeable gap between the barrel and the exposed slide rails.

There was plenty of room for ingress to get into the pistol, and the conical lockup worked well, but under repeated firing, the barrel would heat and expand, presenting issues with the barrel failing to lock up completely. In any case, the Model 1902 was deemed unsatisfactory as, by 1905, the Army wanted a .45. The Model 1905 chambered in .45 ACP featured a barrel bushing machined to fit into the slide. It also served to retain a distinct recoil spring plug housed under the bushing. This was subsequently refined in what would become the Model 1911.

The Move Away from the Barrel Bushing

Time marched on, as did the 1911, but most subsequent handguns, even those based on the M1911, do not have a barrel bushing. Why not? The answer lay in equal parts patent evasion and technological refinements.

When John Browning moved on to create a new high-capacity 9mm handgun that would become the Browning Hi Power, he had to start from scratch as he sold his patent rights for 1911 to Colt Manufacturing. How do you improve on perfection without violating patents? Don’t include those features. The swinging link that served to tilt the 1911 was gone in favor of a single-piece cam that most handguns today use. The barrel bushing and recoil spring plug were also omitted. Instead, the front of the slide alone acted as a barrel bushing against the barrel, and the recoil spring was retained below. The spring could not be released from the muzzle for maintenance, and instead, it was drawn from the rear when the slide was taken off the pistol.

The Era of Precision Machining

Innovations in machine tool technology also made the barrel bushing something of a redundancy. The Colt 1911 was born in an era before CNC or even NC machining. Every part was made on manual lathes and mills to fit a certain specification to ensure some interchangeability. From there, the parts would be hand-fitted with minor polishing or refining as needed to make sure the parts fit together and work as intended. Having a barrel bushing made some sense in the 1911 because it was easier to troubleshoot a small round piece on the bench or swap it out for another instead of wasting setup time reworking the slide. But today, achieving exacting tolerances is achievable with less time and virtually no hand fitting. The Colt 1902’s barrel lockup has since come full circle, and most pistols lock up that way. But if you are in the market for a 1911, there is still the question of whether to go with tradition or usurp it for something newer, though arguably better.

1911 Pistols: To Bush or Not to Bush

Barrel bushings were used sparingly in the early days of the autoloading pistol before they were quickly abandoned. The 1911 remains the only mainstream design that uses them. However, there is no shortage of 1911s that use a conventional barrel lockup and even full-length guide rods like any modern pistol. History suggests we should not entertain getting a pistol with a barrel bushing, but many in the 1911 community say differently.

It is often the case that when engineers seek to shrink or modify a proven design, the new model has problems. The 1911 is no exception. Barrel bushings are among the first things 1911 users change or modify, especially among those who want to accurize their pistol. Despite this desire, some are adamant that the original GI version of the 1911 is the most reliable.

Obsolete?

On the other hand, shooters using 1911 and 2011s with a direct barrel lockup and full-length guide rods have their pros and cons as well. These pistols are touted for their accuracy as the barrel locks directly with the slide, and the recoil spring cannot potentially kink because it is held captive by the guide rod, which runs the length of the action as it cycles. On the other hand, this arrangement requires a tight fit—a fit that might become too tight once the gun heats up. The accuracy you can get from pistols like these might be greater due to the fact that many of them use heavy bull barrels that one might want for competition but not for carry.

The barrel bushing became obsolete once direct barrel lockups were perfected to be tight enough for accuracy but loose enough to ensure good reliability. While it is an extra part to contend with, the barrel bushing does not make the 1911 platform any less reliable, and there are compelling reasons to go the GI 1911 route over a more conventional setup.

The post 1911 Quirks: Barrel Bushings appeared first on The Mag Life.

Read the full article here