D-Day: The Airborne Mission

The Allied airborne drop is among the most famous aspects of Operation OVERLORD. Thanks to the excellent Band of Brothers miniseries, many people perhaps know more about the airborne operations than they do about the main amphibious landings. That knowledge, however, is likely incomplete. Those whose familiarity comes from television and movies only get a partial picture. So, let’s look at the three Allied airborne divisions (yes, three) that jumped into Normandy, their missions, and how they impacted the invasion, though that last one is kind of ambiguous.

Airborne Troops: A New Weapon

The 1920s and 1930s saw the world’s great powers begin experimenting with parachute troops. The US Army began this process in 1928. By 1936, the Soviet Union had over 5,000 trained paratroopers, and both it and the Germans developed doctrine for their use. Germany successfully used parachute and glider forces in Holland and Crete in 1940 and 1941, respectively.

The US got serious about parachute troops in 1939, creating an experimental platoon to hammer out a workable doctrine. That platoon eventually became the 501st Parachute Infantry Battalion (PIB), which later expanded to a regiment (501st PIR) that jumped into Normandy as part of the 101st Airborne Division. The 501st PIB also created and operated the US Army’s first parachute training school.

Other PIBs followed the 501st, expanding to regimental size after the War Department’s order of January 30, 1942. Army planners’ discussions with the British regarding a future invasion of France led to the recommendation for division-sized units. The War Department reclassified and divided the 82nd Motorized Division into two airborne divisions, which were smaller than the standard infantry division. The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were activated at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, on July 30, 1942. The 11th, 13th, and 17th Airborne Divisions were all activated within the next ten months. The 82nd and 101st protected the Normandy invasion’s right flank.

The British, for their part, activated two airborne brigades in 1941. Those brigades eventually became the 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions, collectively known as the “Red Devils” for their distinctive red berets. The 6th Airborne “Pegasus” Division secured the Normandy landing’s left flank.

Mission Disputes

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower had never liked airborne divisions. He liked the idea of airborne troops, but he thought division-sized units were too large and unwieldy. He preferred smaller Regimental Combat Teams. “To employ at any time and place a whole division,” Eisenhower wrote to Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, “would require dropping over such an extended area that I seriously doubt that a division commander could regain control and operate the scattered forces as one unit.” Eisenhower’s concerns were borne out in Normandy.

Ike’s reservations were partially based on the perceived lack of aircraft to support a division-sized drop, much less three simultaneous drops. His reluctance subsided when those aircraft became available in early 1944 since he believed the airborne units were vital to OVERLORD’s success. The change may also have been influenced by US First Army commander Omar Bradley’s assertion that he would not land without airborne forces in front of him.

Marshall, for his part, saw the airborne divisions as strategic-level assets. He was upset when he saw the OVERLORD plan placing all three airborne divisions on the landing’s flanks, essentially a tactical deployment. Marshall told Eisenhower that he was disappointed in the failure to strategically employ the airborne forces. He suggested that all three divisions be dropped on Evreux, near a complex of four airfields about 100 kilometers south of Sword Beach. The airfields could be used to fly in additional troops and equipment so the paratroopers could hold out until relieved by ground forces advancing from the beach.

“This plan appeals to me,” Marshall wrote Eisenhower, “because I feel that it is a true vertical envelopment and would create such a strategic threat to the Germans that it would call for a major revision of their defensive plans.” Marshall said the Germans would be completely surprised and that the resulting airhead would threaten Paris and the Seine River crossings and rally the French Resistance. He said the only argument against it was that something like that had never been attempted, which he found a poor excuse.

But Eisenhower was adamant. He defended the OVERLORD plan and deflected Marshall’s meddling by stating the danger posed by an armored counterstroke into the landing’s flanks if the airborne blocking forces were removed. The Allied Ground Forces Commander, British General Bernard Montgomery, strongly concurred, giving Eisenhower a fallback position.

He countered Marshall’s Evreux suggestion by pointing out how the Germans were past masters at concentric operations utilizing well-developed road networks like those in France. He believed they would quickly isolate and reduce the airhead, thus wasting the airborne divisions. Eisenhower got his way, and the 82nd, 101st, and 6th stayed on the Normandy flanks.

The Plan

The airborne divisions were to guard the invasion’s flanks by disrupting German operations and blocking access to the beachhead. Not every member of the Allied brass was on board. Eisenhower’s Air Commander, British Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, believed the airborne divisions would be slaughtered and implored Eisenhower to reconsider dropping them. Eisenhower listened to Leigh-Mallory but concluded that he had no choice but to deploy them as planned. Leigh-Mallory argued this point until the invasion launched.

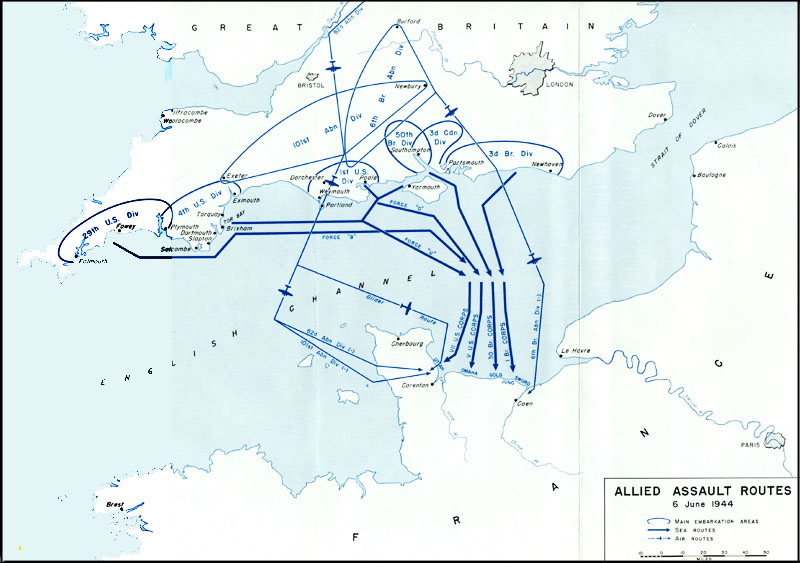

13,400 American and nearly 7,000 British parachute and glider troops dropped in the early hours of June 6. Each division had a unique mission that directed their actions on D-Day and after. Those missions dictated their deployment areas and drop zones. Let’s look briefly at each division’s mission, moving east to west. We begin with the British.

The 6th “Pegasus” Airborne Division

The Red Devils were assigned to protect the invasion’s eastern flank, just inland from Sword Beach, where the British 3rd Infantry Division would land. The primary mission was to seize bridges across the Caen Canal and the Orne River, destroy bridges over the Dives River, which was farther east, and hold the ridge between the Orne and the Dives. They were also to destroy the German artillery battery at Merville.

The Merville Battery was taken, despite the landing force being badly scattered, only 15 minutes before the Royal Navy was to begin bombarding it. Those shells were directed toward other targets once British Lt. Colonel T.B.H. Otway’s depleted force sent up the flare, marking the assault as a success. Otway suffered 50% casualties, but the battery was silenced. Unfortunately, the guns were found to be old and did not pose a serious threat to Sword Beach. But Otway’s 9th Battalion Red Devils did their job.

The most famous and perhaps the most spectacular success came early. Major John Howard commanded D Company, 2nd Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, the “Ox and Bucks.” Howard’s glider company was assigned to take the bridge over Caen Canal, just east of Sword Beach. The bridge lay on the same road as the bridge over the Orne River, some 600 yards away. The gliders assigned to each bridge landed on the strip of land between the bridges. The bridges were taken to both facilitate the Allied expansion and to block German reinforcements, especially the 21st Panzer Division.

The Caen Canal bridge was defended by a 50mm anti-tank gun, a concrete pillbox, dug-in machine gun emplacements, and coiled barbed wire. It was wired for explosives, which were later found to have been removed.

Howard’s lead glider landed just 70 yards from the bridge, its nose piercing the protecting barbed wire, making a gap. It was 12:18 AM on June 6. D Company stormed the bridge and took it in just 14 minutes. The assault yielded the first Allied combat casualty and combat death on D-Day. The more lightly defended Orne River bridge was also stormed and quickly taken. The Ox and Bucks fought off two German river gunboats and survived a dud German bomb that may have brought the bridge down. They were aided by 7th Battalion paratroopers who landed to the east and blocked German attempts to retake the bridges.

The German 21st Panzer Division was ready to move. Its 125th regiment, commanded by Colonel Hans von Luck, planned to hit the beaches before the Allies could get ashore. But Hitler retained control of the panzer divisions, and Luck had no authority to move. Paralyzed by an absent commander and a dysfunctional command structure, Luck stayed where he was.

Howard’s men held on and were relieved on the evening of June 6 by the 7th Battalion and the Commandos of Lord Lovat’s Special Service Battalion. The bridge was renamed “Pegasus Bridge in the 6th Airborne’s honor. The Pegasus Bridge Café stands nearby. The Orne River Bridge is called “Horsa Bridge,” after the Horsa Gliders that bore the British soldiers. Each bears the 6th Airborne’s unit insignia. A service is held every year at midnight on the spot where the lead glider touched down, led by Howard’s daughter. The assault on Pegasus Bridge is recreated in the 1962 movie The Longest Day.

The 101st Airborne Division, the “Screaming Eagles”

The American 101st Airborne was tasked with helping to open Utah Beach. Utah was the extreme right flank of the invasion force, and it faced west across the Cotentin Peninsula. The Germans had used irrigation apparatus to flood the areas behind the beach, creating a series of bottlenecks on the causeways connecting inland.

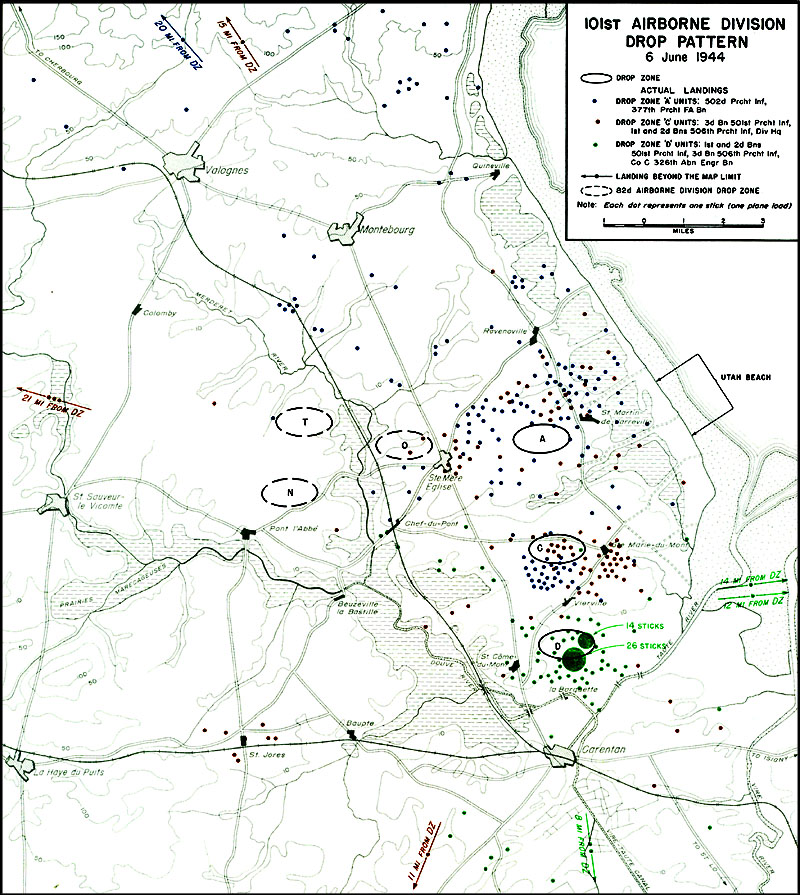

The 101st’s job was to attack the German emplacements guarding those causeways from the rear, allowing the American 4th Infantry Division to move off the beach. Furthermore, the division was to seize vital crossroads and bridges over the Douve River to the south near the town of Carentan. The 101st’s three regimental drop zones reflected those mission tasks.

Poor visibility and anti-aircraft fire scattered the 101st’s drop all over the area, hampering the mission from the beginning. Many 101st troopers landed in the 82nd’s area, and vice-versa. Fortunately, the 4th Infantry Division landed some 2,000 yards south of their assigned landing spot on Utah, placing it more in line with where the 101st ended up. But only one causeway, Causeway “B,” could be used to exit the beach. Causeway “B” was opened, however, and the amphibious troops were well inland by day’s end. Part of the fight to open Causeway “B” is portrayed in the Band of Brothers miniseries, where Easy Company assaults and silences the German battery at Brécourt Manor.

The 101st’s combat effectiveness was greatly hindered by the scattered drops, and the Douve River crossings were not taken on D-Day. But the scattering paid unforeseen dividends, which we’ll address after touching on the 82nd.

The 82nd Airborne Division, “All-American”

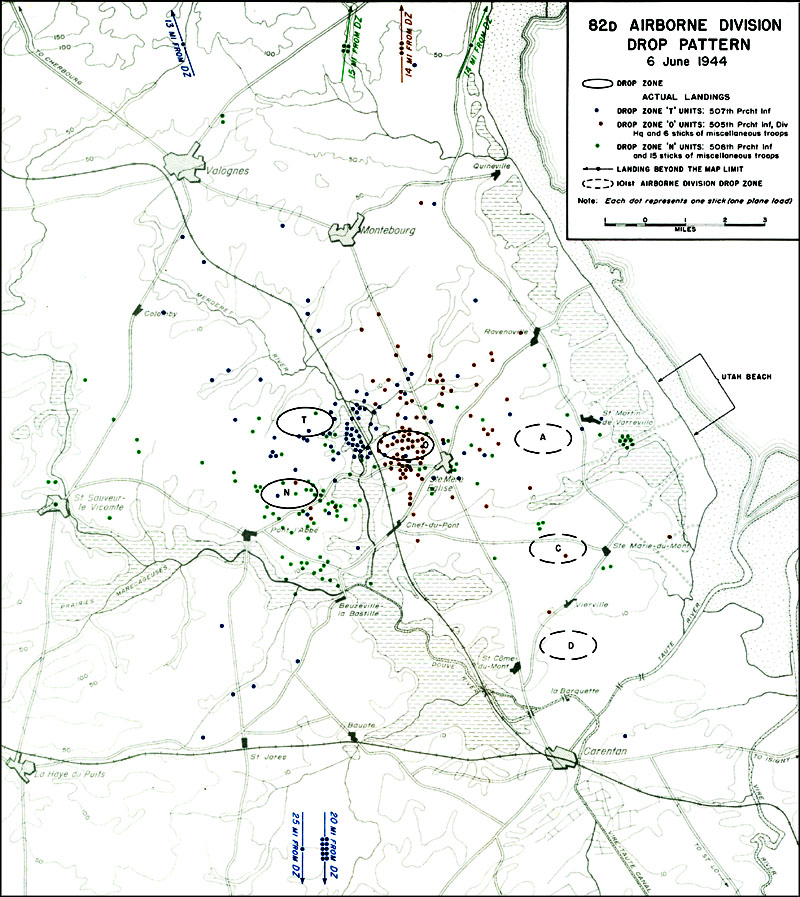

The 82nd Airborne Division dropped west of the 101st. Where their sister division looked east and south, the 82nd looked primarily west. Their mission was interdiction rather than direct combat support. The 82nd was tasked with seizing the vital road junction at Ste.-Mére-Église, destroying the upstream Douve River bridges, and establishing bridgeheads across the Merderet River. This was meant to seal off access to the Cotentin from the south.

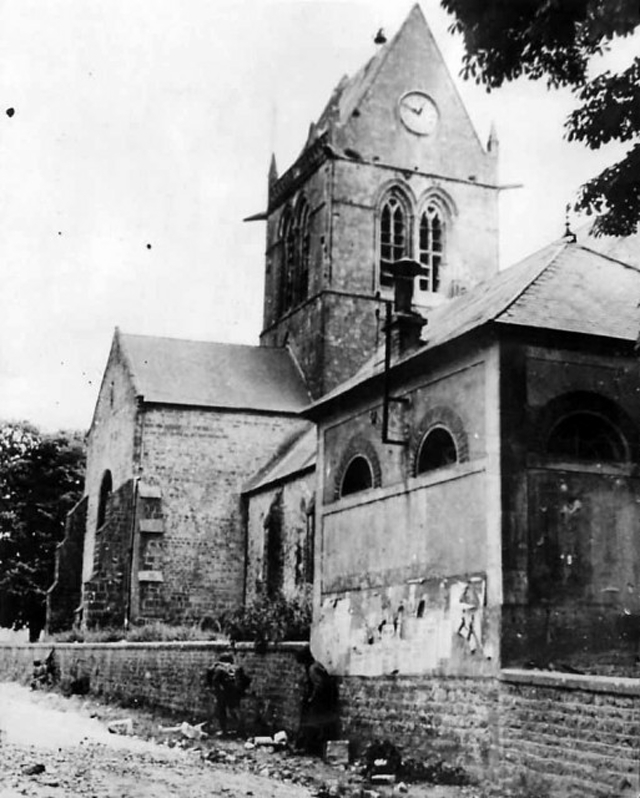

The first task was accomplished thanks to an accurate drop and hard fighting. Lt. Colonel Edward Krause’s 3rd Battalion, 505th PIR landed mostly northwest of the town and took it quickly, cutting the main highway from Cherbourg to Caen. They fought off determined German counterattacks throughout the day to hold the town and prevent the enemy from concentrating there. The Longest Day also recreates the drop on Ste.-Mére-Église.

But the 507th and 508th PIRs, dropped west of the Merderet, were badly scattered. The 505th’s 1st Battalion was tasked with securing the east bank, which it did, but the regiments on the west bank were unable to concentrate. Several attempts to force the river failed, and the bridgeheads were not established until later. Elements of the 508th, however, stopped a determined attack by units of the German 91st Division, saving the crossing points and keeping the Germans west of the Merderet.

Most of the 82nd was scattered all over the lower Cotentin. It took days for the two American airborne divisions to assemble into a coherent fighting force. But there were some positives.

Confusion

If the 82nd and 101st were tangled up, so were the Germans. Many American paratroopers assembled in small, mixed groups, and fought the Germans where they were. They were usually not in contact with their commanders or neighboring groups. This created confusion in the German command as they tried to make sense of what they saw. The American troopers appeared to be everywhere. The cluttered picture hampered the German efforts to mount a coherent defense in the Cotentin, as their units were harassed or even cut off by the Americans. American commanders would have preferred fighting concentrated, giving them a chance to achieve their objectives, but confusing the Germans was a positive result.

Outcomes

Though the 82nd and 101st were in no shape for offensive operations, they accomplished two important tasks: opening Causeway “B” from Utah Beach and taking and holding Ste.-Mére-Église. Holding the Merderet’s east bank was less than the planners hoped for, but it was a positive given the circumstances.

All three airborne divisions performed well under trying circumstances. Many of the first day objectives were not met. But the beachhead’s flanks were secure and became more so as the units assembled over the next few days. German command deficiencies certainly aided the situation, as did Allied air supremacy.

Normandy did not prove or disprove the efficacy of airborne divisions. But those units did the job that Eisenhower, Montgomery, and Bradley felt so necessary. Airborne divisions were employed in various roles over the next 11 months until Germany surrendered. The 82nd, 101st, and British 1st Airborne were used to leap through Holland, boldly attempting to open the way for armored forces to cross the Rhine into Germany itself. As in Normandy, results were mixed, though the operation’s ultimate goal failed. The 101st famously showed its mettle in the Siege of Bastogne, while the 82nd slogged its way through the hellish Hürtgen Forest.

Eisenhower himself was not disappointed in the airborne part of OVERLORD. He was well aware of the old maxim that no plane survives first contact with the enemy. 80 years later, the three airborne divisions’ accomplishments are rightfully celebrated. Some 20,000 men dropped into the dark, not knowing what was on the other end. Most didn’t land where they were supposed to. Yet they stood up. Some made it to their objectives. Some fought where they were.

No one can say whether the Germans would have been able to assault the beaches had the paratroopers and glider troops not been there. All we know is that they were not able to do so as things stood. Maybe we should ask the Germans at Ste.-Mére-Église, Causeway “B,” and Pegasus Bridge whether the Allied airborne troops were effective. I think I know what their answer would be. Never forget.

The post D-Day: The Airborne Mission appeared first on The Mag Life.

Read the full article here